Revealing the Empowerment Revolution a Literature Review of the Model Cities Program

Essay

The Model Cities plan was the terminal major urban aid initiative of the Great Society domestic calendar of President Lyndon Johnson (1908-73). The legislation called for the coordination of federal services to redevelop the nation'south poorest and to the lowest degree-served urban communities. In 1967, N Philadelphia was designated for renewal nether this program. Rather than serving to unify policies, notwithstanding, the question of how to combine redevelopment with citizen participation exposed not simply the inadequacies of the federal program but likewise the widening racial error lines between white elected leaders and the city's African American communities.

The national program's origins can exist traced to a memorandum that Walter Reuther (1907-70), president of the United Motorcar Workers Union, sent to President Johnson in May 1965. In bold language the labor leader encouraged the president to launch a comprehensive attack on the structural, social, and economical roots of poverty in six "demonstration" cities. The appeal's rhetoric struck a chord with a president eager to build non just houses, merely communities worthy of citizens who lived in his Great Club. In September, Johnson directed Robert Wood (1923-2005), secretary of the new Section of Housing and Urban Evolution (HUD), to chair a task force of industry executives, intellectuals, politicians, and administrators, to bring Reuther'southward proposal to life.

Model Cities evolved in response to the concerns of urban mayors who had grown weary of the Community Action Programs (CAP) created by the Economical Opportunity Act of 1964. Charged with securing the "maximum feasible participation of the poor" in antipoverty programs, CAPs were largely run by private and nonprofit organizations. Relatively gratuitous from oversight and political control, they had the potential to become a new base of operations for empowering poor and minority residents. Model Cities attempted to rectify two competing concerns. It sought to address African American dissatisfaction with federal urban renewal policy by instituting new comprehensive measures; still, information technology failed to ascertain clear lines of leadership and authority. Increasing racial tensions, sparked by riots that spread throughout American cities in the late 1960s, added a sense of urgency to the program's pattern while the escalation of the wars in Southeast Asia tuckered funding for social programs, limiting room for political maneuvering.

In an endeavor to leverage congressional support, the task force expanded the plan to lx-six cities at a price of $two.3 billion dollars. When the president unveiled the program in Jan 1966, it quickly met resistance. Critics railed at the program's cost and accused the president of catering to antiwar and African American demonstrators. Those sympathetic to the beak asserted it was too small to seriously accost the challenges of the urban crisis. Prospects for the bill'due south passage seemed grim, simply Johnson intensified his lobbying effort to secure the necessary votes. In its final form Model Cities were created in 150 locations while the final appropriation was reduced to a mere $900 one thousand thousand dollars. When signed into police on November three, the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966 mandated a stringent timeline for submitting planning grants, simply only vaguely outlined the terms for community participation, while asserting that local elected leaders would maintain ultimate authorisation.

Mayor Tate Lobbied for Model Cities

Several Philadelphians were influential in the passage of the Model Cities legislation. Mayor James Tate (1910-83), who too served as the president of the National League of Cities, lobbied for the bill's passage. William Rafsky (1919-2001), vice president of the Former Philadelphia Development Corporation, served on the job force that drafted the legislation, while Democratic Congressman William Barrett (1896-1976) introduced the nib in the House of Representatives and so negotiated a compromise with Republican members of the Subcommittee on Housing to clinch its passage. Confident that this insider participation would deliver a substantial share of the new appropriations to Philadelphia, Tate instructed city planners to concurrently draft the city'due south grant asking. Equally a outcome, Philadelphia became the only city to run into the programme'south February 1967 borderline. However, in its haste it failed to consult any of the quarter 1000000 people who lived in the target neighborhood of North Philadelphia.

When the city finally sought community back up, urban center activists, including Alvin Echols (b. 1931), expressed wariness and demanded guarantees that they would play a meaning office in the planning procedure. Echols, director of the North City Congress, a coalition of l-eight local organizations, proposed the area'south customs structures be incorporated every bit equal partners in the city's planning process. Eager to comply with federal guidelines in a timely fashion, Tate agreed. On April 29, 1967, approximately 500 neighborhood representatives voted to form the Area Broad Council (AWC), a federation of 125 customs organizations, every bit the community arm of the Model Cities program. William Meek (1921-95), an educator, social worker, and assistant director of the Wharton Eye, a North Philadelphia Settlement House, became the council's first manager.

The AWC represented a diverse customs through a network of sixteen neighborhood "hubs." While this structure ensured the broad representation of community organizations and individuals, its dull-moving democratic nature proved incompatible with the requirements of professional planners. Factions apace formed inside the quango as radicals pursued a confrontational strategy of applying pressure on City Hall with position papers and public demonstrations. As a issue, the two sides developed a mercurial relationship punctuated past communication breakdowns and the replacement of the starting time iii Model City administrators. Speaking at the Third International Black Power Conference, held in Philadelphia in the fall of 1968, Robert "Sonny" Carson (1936-2002) applauded the radicals' efforts to plan from the lesser-up and resist the power of white politicians. AWC moderates worked tirelessly to preserve relationships with elected leaders, and in December 1968 successfully negotiated with the city's Economic Development Unit to submit a proposal in accordance with HUD's guidelines. This compromise plan, which called for creating seven community corporations (four controlled by the AWC), represented the high point in the urban center and council's relationship

The council'south tenuous position was revealed in 1969 when Goldie Watson (1909-94) was named the fourth Model Cities administrator. A close ally of Mayor Tate, Watson was a seasoned political operative and a resident of Due north Philadelphia. A teacher and small business owner with deep roots in the community, she challenged the AWC'south position as a representative voice. The election of Richard Nixon (1913-94) to the presidency that same year dramatically contradistinct the operation of federal anti-poverty programs. Once a champion of denizen participation, HUD reversed class and mandated that federal funds exist channeled through established city institutions. This shift in policy dovetailed neatly with Watson'southward management of Model Cities. In an endeavor to consolidate her position, she consigned the AWC to an advisory role, diminished its representation in the community corporations, reduced its budget, and implemented new policies and bookkeeping procedures to curb the activism of its increasingly fractured and radical membership.

Area Wide Council Files Suit

Convinced that Watson aimed to undermine the role of citizen participation, William Meek rejected the new structure and protested Tate and Watson's undemocratic ability catch. The AWC filed adapt in August 1969 accusing the city of violating provisions of the Demonstration Cities Act by not including a representative community voice in the planning and implementation procedure. The refusal of hardliners to negotiate with the city proved costly as the AWC lost vital public back up. When the case was dismissed in November 1969, Watson seized the reward, announcing the formation of a new interim denizen'southward committee that included 19 quondam AWC members. With its reputation in ruins, and its membership depleted, Meek and the AWC continued to fight. A protracted legal battle ensued. When the AWC emerged victorious in July 1970, it could claim simply a pyrrhic victory. The legal battle to ensure community participation left the council in ruins while the city connected to implement the Model Cities program without the council's input.

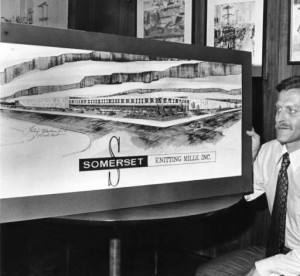

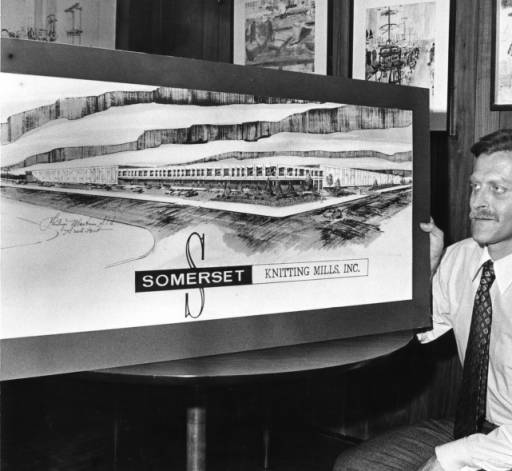

Watson and her associates molded the Model Cities programme into a tool of political patronage. With some exceptions, their efforts were typically pocket-size in scale, exorbitant in price, and failed to involve the community in whatsoever meaning fashion. By 1972, these practices provoked charges of widespread abuse and nepotism prompting HUD to threaten the termination of all funding unless meaning changes were fabricated. Seeking to retain federal monies, the recently elected mayor, Frank Rizzo (1920-91), initiated new policies and directed the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) to atomic number 82 a reorganization of the Model Cities program. Under PIDC'southward direction, Model Cities concluded its efforts to develop Black capitalism in favor of a new strategy that supported and retained existing businesses. The PIDC-Model Cities partnership financed the relocation of the Somerset Knitting Mills Company, saving 400 jobs, the beginning in a series of inner-urban center industrial development projects.

In 1974, after near 8 years of halting progress, this idealistic, aggressive, and contradictory federal policy was discontinued and replaced with a organisation of community development cake grants. Critics and supporters alike agreed that funding was spread too thin to be effective. In some communities Model Cities launched a new era of identity politics and opened avenues for minority leaders to pursue careers in public service. In Philadelphia, minority residents who had been historically denied access to the ability and resources to shape the hereafter of their community, found it hard to penetrate the existing white power construction. While Blackness capitalism received a pocket-size boost, the program's lofty promises were compromised by hardened racial lines, ineffective leadership, greed, mismanagement, poor supervision, ineffective internal controls, and poorly delineated lines of potency. These internecine battles took center stage, leaving the vision of comprehensive urban renewal a casualty in the ongoing struggle between City Hall and advocates of community control.

Jason T. Bartlett holds a Ph.D. in history from Temple University. His dissertation, "The Politics of Community Development: A History of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation," examines the fifty-year history of the nation'due south first comprehensive community development corporation. (Writer data current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- People Places: The Buildings Model Cities Built (PublicResource.org)

- Lyndon Johnson and the Great Society (U.S. Department of Land Country Studies)

Source: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/model-cities/

Post a Comment for "Revealing the Empowerment Revolution a Literature Review of the Model Cities Program"